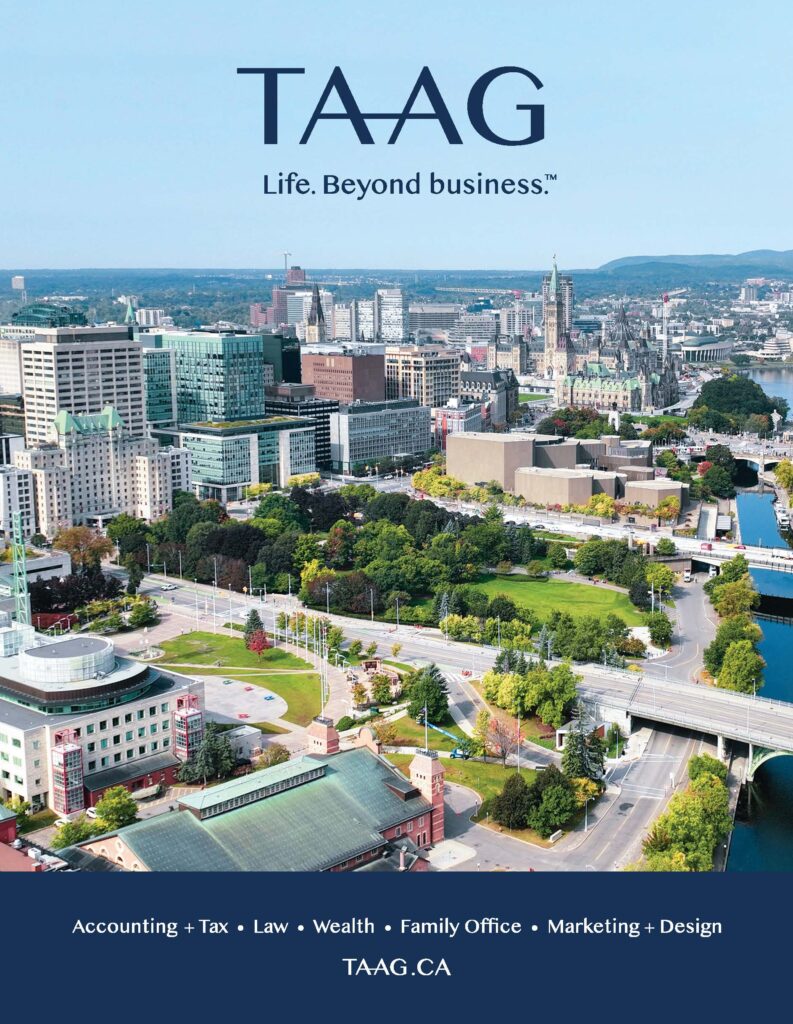

Building the Capital: Where Old Meets New

How Zibi Plans to Transform the Ottawa-Gatineau Riverfront

The former Domtar lands between Ottawa and Gatineau still look “full of potential” but there are subtle signs that change is coming. Despite the complexities that arise from the metamorphism of a derelict industrial site, a new development project is emerging.

Zibi is an ambitious redevelopment plan by Windmill Development Group and Dream Unlimited Corporation. The Ottawa River and the nearby Chaudiere Falls have long held an allure for the surrounding communities, from the Algonquin-Anishinabe people who needed to portage around the falls, to the log drivers who traversed the river, to the local pulp and paper mills that fought to harness their operations with its strong current.

Now, a handful of industrial buildings that once supported the pulp and paper industry have been converted into event spaces that have already hosted trade fairs on sustainability, free yoga classes, and a fundraiser for Syrian refugees. A high-tech sale centre showcases what the waterfront development will offer, and site preparation has started in earnest.

With this work underway, the partners behind Zibi are tackling a new kind of challenge—turning a contaminated heritage site into a sustainable urban community, in consultation with three different levels of government and diverse community interests.

“It’s a complicated property, but it’s worth it,” says Rodney Wilts, a Zibi partner from Windmill Development Group.

An intricate mix of authorities, including the City of Ottawa, the City of Gatineau, and the National Capital Commission, governs the redevelopment. But that hasn’t deterred Wilts, who credits community consultation for the progress they’ve made so far, including the first-ever joint design panel with all three jurisdictions.

The name Zibi comes from the Anishinabe word for river, and the project is meant to respect the significance of the land to Algonquin-Anishinabe people. The development is also one of only ten in the world (and the only one in Canada) to be recognized as a One Planet Community, a measure of ten sustainability principles that touch on everything from construction materials to health and happiness. Among other things, the Zibi master plan calls for a district-wide energy system that will provide zero-carbon energy by 2020. Members of some Algonquin-Anishinabe communities have established an advisory council on First Nations issues, and Algonquin companies in Quebec have partnered with Zibi to hire First Nations workers. Overall, it’s a huge undertaking, but Wilts believes Ottawa is ready for it.

“Ottawa is at an interesting inflection point,” he says. “We’re not the only big development underway right now.” He points to Lebreton Flats and Lansdowne Park, among others, as signs that Ottawa is becoming increasingly urban.

However, there is still much to do. Zibi will unfold in six phases over ten years. Support for the redevelopment is not universal, and several Algonquin communities actively oppose the project. Zibi’s backers will need to address critics who see the development as an elaborate green-washing

exercise, and who note that despite the value claims, the price to buy into Zibi will make it inaccessible to a large segment of the market. There’s also a lot to learn about construction.

“We’re learning a lot about these old buildings,” says Wilts. “They’re expensive to upkeep and they’re expensive to restore.” But he’s reminded of what author and urbanist Jane Jacobs once wrote: “New ideas must use old buildings.” He hopes that Zibi will showcase the best of both, in a way that satisfies the entire community.