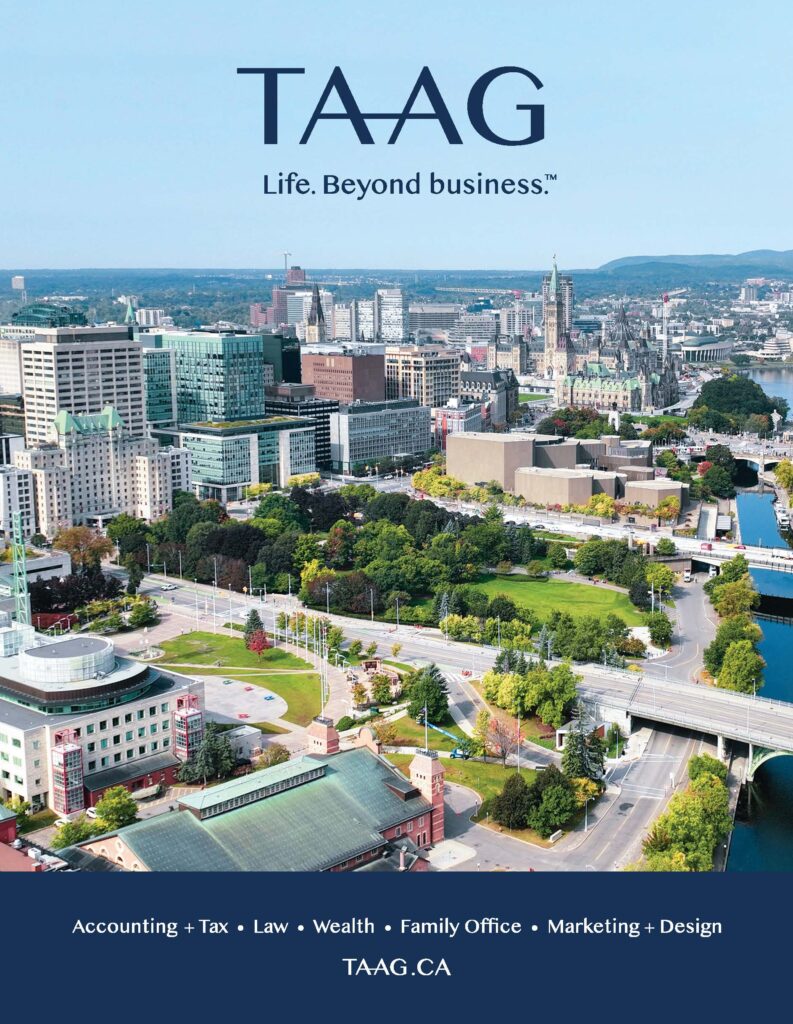

Building The Capital: The Little City That Grew

The Ottawa LRT will include a 2.5-kilometre tunnel underneath the downtown core

Ottawa’s infrastructure might be expensive, but that’s the price of growing up

By Emily Mathisen

From flashy projects like the $2.1-billion Light Rail Transit (LRT) system’s Confederation Line to the more prosaic combined sewage storage tunnel, the City of Ottawa has initiated some major infrastructure improvements in recent years.

The projects are plentiful and expensive: The city’s net debt has doubled since 2010 to fund them. But they are also necessary. “People used to say that Ottawa was the big little city, but now we’re turning into a little big city,” says John Smit, the City of Ottawa’s acting director of economic development. “The city of Ottawa has really come of age.”

Many of the infrastructure projects come from the city’s “Building a Liveable Ottawa 2031” consultation process, which stressed that denser communities generally have fewer health problems than communities designed for cars. Still, health benefits are not the only advantage; denser spaces also cost less. The 2013 Transportation Master Plan, for instance, calculates the cost of carrying one person one kilometre by different modes (taking into account the costs to government, users, and society of collisions and pollution; but excluding user time). Cars cost $0.716 per km, public transit $0.592, and cycling $0.159. Predictably, the automobile is the most expensive form of transportation.

John Moser, the City’s general manager of planning and growth management, hopes to see the use of cars decline to 50 percent once the Confederation Line opens. “The city has put a lot of effort into increasing walking and cycling,” Moser says, noting that the city has been following this strategy for years—at least the last two turns of council.

“Yes, we will still be able to drive. But we want to make it easier for people to not use their cars—to make it easier for them to use transit,” he adds. Once the Confederation Line opens in 2018, getting downtown from points east and west will be much more convenient.

Although the Building a Liveable Ottawa strategy is relatively new, the construction of an LRT line has been decades in the making. “The old bus rapid transit system was built with a view that it would be transformed to a rail transportation system, says Smit. “Now that we’re approaching a million people, it’s time.”

The city projects that Ottawa’s population will grow 30 percent by 2031, and that by 2048, the LRT project will have saved $1.5 billion in time, $1.1 billion in vehicle operating costs, and $400 million through accident avoidance. That being the case, Smit says, the LRT will significantly support the city’s overall economic growth.

In fact, the LRT may already be boosting growth: So far, some $900 million of the $2.1- billion project is being paid to local firms and subcontractors. The city is also working to attract development around the Confederation Line stations, by altering zoning to promote increased density.

This is especially evident around LeBreton Flats, which will be served by the Confederation Line. Planned in consultation with the Algonquin community in the area, it will have an aboriginal theme. The location will also improve transit connections with Gatineau.

One of the natural highlights of the neighbourhood is the spectacular Chaudière Falls, which has been inaccessible to the public for many years. That will change with the arrival of the neighbouring Zibi development, a sustainably designed multi-use community of condos, townhomes, parks, and commercial and retail spaces. In summer 2017 a lighting display is planned to showcase the falls, as part of Canada’s 150th birthday celebrations.

But for decades, the area has been run down.

“We hope to re-stitch this area into centre of the downtown, to bring it back into the fabric of the city,” says Smit. “The Chaudière Falls is an iconic feature, and we want people to see what it’s all about.”