Pandemic Real Estate Boom Affirms Desirability of Ottawa Lifestyle

The Ottawa residential and industrial real estate markets have illustrated amazing resilience against severe headwinds caused by the global pandemic’s devastation, which included sudden lockdowns, social distancing requirements, and unprecedented economic shocks.

Debra Wright, president of the Ottawa Real Estate Board (OREB), says the local real estate boom in sales and prices during the pandemic was totally unexpected in the profession.

“When things first shut down I was very concerned,” says Wright, who is also a real estate broker and brokerage owner. “I really thought the market was going to completely slow down. So it was a surprise when, in the first few days of shutting down, I had clients calling me saying ‘I’m not working. I want to go look at houses.’”

Initially there was a sense, particularly among investors and other buyers, that this was going to be an opportunity to seek bargains because a drop in demand could lower prices. But “as the economy opened up a little bit and it became clear that REALTORS ® were going to become essential workers, the market just seemed to take off,” says Wright.

The Ottawa real estate market has appeal because it is backed by a strong insulated economy. The federal government is located here. The city also has a strong tech sector, and various spin-off businesses that support the main industries. As a result, many people have high incomes. Furthermore, outside investors find Ottawa’s historically low prices, in comparison to other major investment centres, appealing. Residents have traditionally been conservative purchasers of homes, purchasing well below their price range, Wright says.

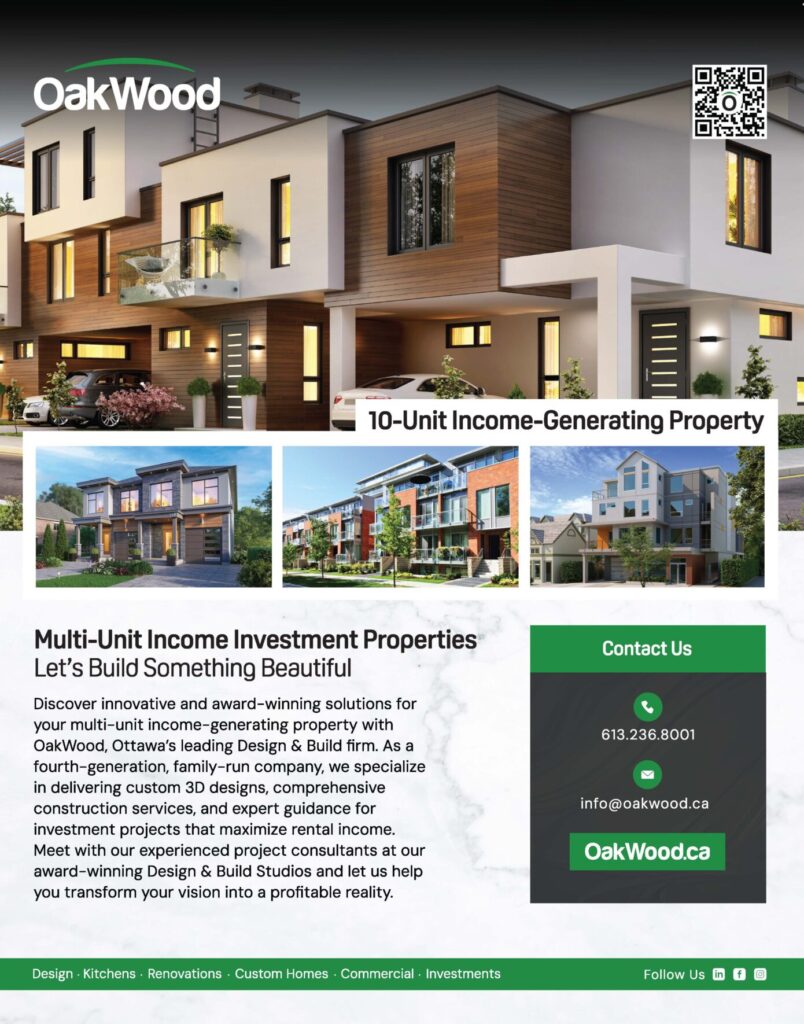

But Ottawa had also experienced a low housing supply for many years, which led to a pent-up demand. And during the pandemic, people started to develop a desire to have larger yards for family recreation. Swimming pools, which had never previously been a major attraction locally, suddenly became very desirable, she adds.

Sales have been strong in nearly every neighbourhood in the central part of the city. Some less developed areas in the core, such as Little Italy, Chinatown and Vanier, are also becoming more attractive to investors and are starting to see redevelopment, which will continue into the future. Areas in the far west end in Stittsville/Kanata, the east end in Orleans, and Barrhaven to the south, that have potential for more development, are also “growing in leaps and bounds,” says Wright.

She notes that prior to the pandemic, average annual growth in house prices was about six to seven per cent. But year-to-date through to the end of October 2021, residential homes, including townhouses, semi-detached and detached homes, increased by an average of 24 per cent. Condominiums, which can include apartments, townhouses, semi-detached and sometimes detached homes, increased by an average of 16 per cent.

The year-to-date average price on a condominium through the end of October is currently about $419,500, while the year-to-date average price of a residential property is about $720,150, says Wright.

“Affordability is something that we’re always concerned about. We need governments to look at the issue of affordability and a part of that is going to be looking at providing resources to increase supply. As long as we have a supply shortage affordability’s going to be an issue,” she notes.

Over the next couple of years, “we expect and hope that home prices will level out a bit as the economy stabilizes, and then go back to continuing with annual moderate growth,” says Wright. “But it’s hard to know at this point. There are so many other factors going on in the economy that we’re not sure what’s going to happen.”

Louis Karam, senior vice-president and managing director of CBRE Limited in Ottawa, says the pandemic has had a large impact on the local office real estate market.

Unlike residential real estate, the office market was hard hit. “We have seen a major slowdown, with most of our towers being emptied out and shut down during the pandemic. In Ottawa the vacancy rate went from 6.6 per cent in the first quarter of 2020 to 9.7 per cent in the third quarter of 2021,” says Karam.

Net rental rates for offices have remained stable over the pandemic. The vacancy rate in downtown Ottawa is currently at 10.5 per cent, which is comparatively low – the third lowest in North America behind Toronto and Vancouver, he says.

But on the industrial side, including manufacturing, storage and distribution properties, local vacancy rates, in response to accelerated e-commerce growth during the pandemic, are at an all-time low, having dropped from 2.7 per cent in the first quarter of 2020, to two per cent in the third quarter of 2021.

This has driven an increase in net rental rates for industrial real estate in Ottawa. At the end of the third quarter, the average rates were $11.94 a square foot, the second highest average net rent in Canada after only Vancouver, says Karam.

“We are seeing two sectors that are faring very well. The tech sector continues to grow and the e-commerce logistics tenants have done well,” says Karam.

CBRE’s 2021 North American tech talent report, issued in July 2021, ranked Ottawa as the tenth best tech talent market on the continent. “We are expecting the tech sector to help lead the way to recovery in the next few quarters,” says Karam. “The office market has been hit across the board. It’s encouraging to see the tech sector faring well.”

As more employees begin to return to the office, vacancy rates are showing a slight improvement. The third quarter of 2021 is the first quarter since the end of 2019 – before the pandemic – that has seen a drop in vacancies. The vacancy rate of 9.7 per cent represents a minimal 0.1 per cent drop from 9.8 per cent, says Karam.

As local vaccination rates increase and corporate vaccination policies are rolled out to coincide with a return to office, “we feel that in 2022, we’re going to see an overall rebalance and increase of momentum. Tech will be at the front of the pack, because we’re seeing firms with large growth there,” he adds.

Although the hybrid working model that already existed pre-pandemic was abruptly accelerated by the pandemic, and will definitely be here to stay, “our view is that the office is still going to be a major part of how companies run. In general, companies with a high growth rate want their people together. So we believe the office will be a part of our future, but the way we use it will also change,” predicts Karam.

“On the industrial side, we’ve seen Ottawa’s potential as an industrial hub become increasingly apparent over the last year, and growth is expected to continue. We’re expecting e-commerce and logistics to continue accelerating. We’re also expecting to see grocery companies looking for space to expand home delivery services that became popular during the pandemic,” he says.

However, on the industrial property side Ottawa “is in dire need of new supply and new construction. And we’re seeing great concern right now over rising inflation and construction costs. That can put a hold on and delay future and even ongoing projects,” Karam warns.