Optimistic Ottawa: A Season Of Growth Ahead

Three experts say Ottawa is well positioned to come out of the pandemic and weather any economic downturns that are looming due to interest rate increases.

BY JENNIFER CAMPBELL

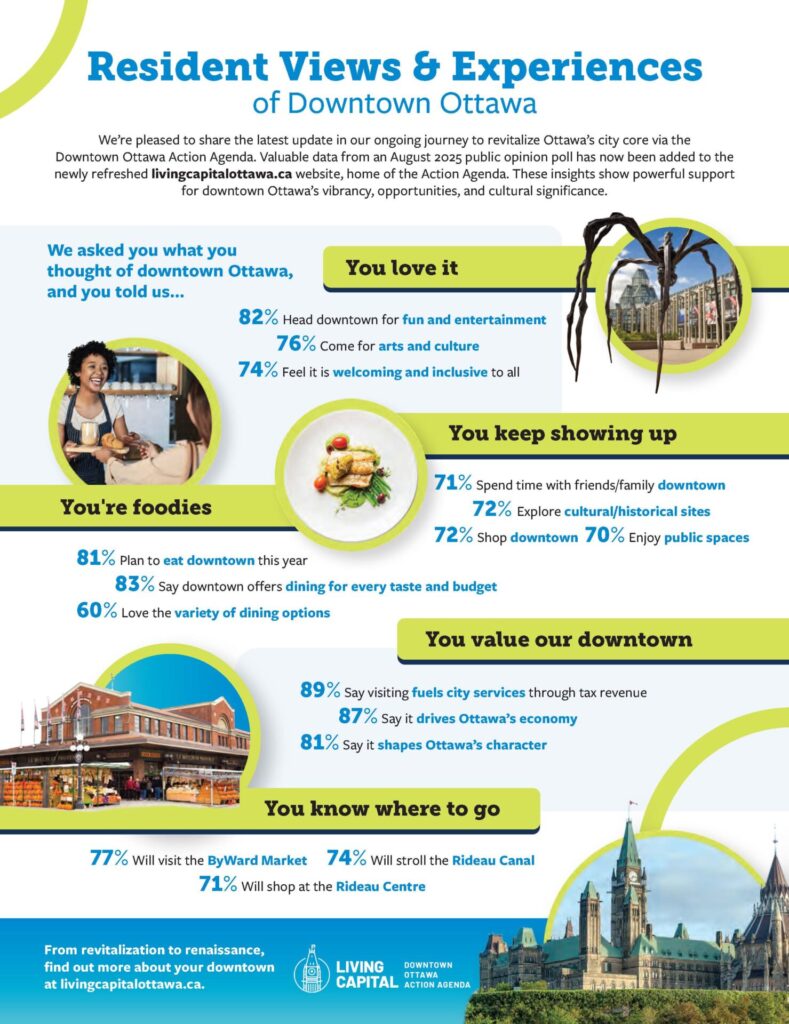

AS A POSSIBLE recession looms, Ottawa’s economy is suffering in the same way the national economy is, but the Canadian Chamber of Commerce’s chief economist says things are a little rosier here than in other Canadian cities.

Stephen Tapp, who also runs the Business Data Lab for the Chamber, says Ottawa is in good shape business-wise.

“At least for the current situation and looking ahead for the next year, the outlook for Ottawa’s economy is really strong and it’s actually among the best in the country,” Tapp says.

He’s been working with Statistics Canada on its Canadian Survey on Business Conditions (CSBC), which is a quarterly survey of up to 18,000 companies.

“When we did the city’s metro-level analysis, 80 percent of Ottawa businesses are saying they are optimistic about the year ahead, ” Tapp says. “That’s considerably higher than Toronto where it’s only 58 per cent. Across Canada, that number is 68 per cent.”

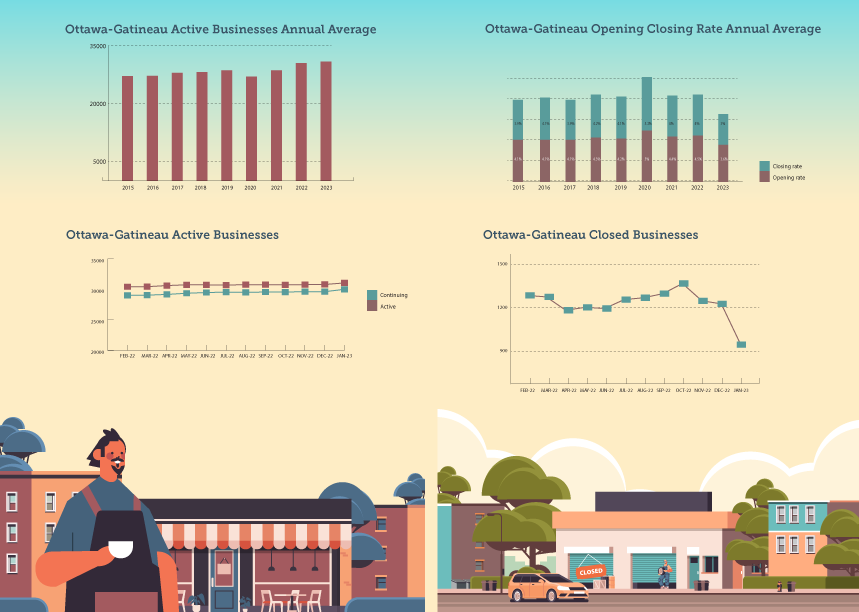

The number of businesses currently operating in Ottawa is also up above pre-pandemic levels. Currently, there are 30,900 businesses operating in the city and the year-over-year numbers on growth rates are better in Ottawa than they are nationally.

“There’s also a higher share of businesses in Ottawa that say their revenues were up in 2022 versus 2021,” Tapp says. “We have 69 per cent in Ottawa saying revenues were up. That’s above the national average, which was 66 per cent.”

Tapp says labour markets are also encouraging with the region’s unemployment rate below the national one.

“Of course, the big wild card would have been the strike with PSAC,” he says. The union and government settled the strike within 13 days and employees have since returned to work. “If that were to carry on for a long time, that would [have been] disruptive.”

Return-to-the-office policies were a key complaint for employees, and Ottawa is definitely lagging behind other metropolitan centres on getting people back to their desks, but most of that ghost-town effect appears to be on the Gatineau side.

Tapp, who works downtown at Slater and Kent Streets, says he notices a lot more foot traffic in the SoPa district than he did a year ago. And he expects travel and tourism to rebound in 2023, too, with a good outlook for attracting American visitors with the weak Canadian dollar while spurring Canadians to book domestic vacations.

On the housing front, prices “went crazy” in Ottawa with the average home price jumping from $550,000 to $750,000. After that “big bump,” they’ve cooled, but they’re still averaging at $600,000, which remains higher than it was before the pandemic.

“If you owned a home before the pandemic and didn’t have to sell your house, you’re in a better position now than you were before the pandemic, other than the fact that interest rates have gone up to deal with inflation,” he says. “The overall price of houses has still gone up.”

And, according to research and analysis by Deloitte, housing starts continue to grow and Ottawa’s job market is outperforming averages, with an unemployment rate of four per cent versus five per cent nationally.

But there are some clouds on the business investment side, which is causing Ottawa to lag behind the national average according to Matthew Stewart, director of economics at Deloitte Canada.

Stewart says companies are concerned about short-term economic performance so they’re cutting back a bit, and there’s the longer-term trend of weak business investment nationally, though those numbers have nudged up.

“I would say Ottawa is lagging the national average mostly because of business investment,” he says, defining investments as buildings, machinery, construction and engineering projects undertaken by businesses. “Statistics Canada tracks volumes of construction and Ottawa is not doing great. It’s fallen in each of the last 12 months in terms of construction. In January, which is the most recent data, [industrial and commercial construction] are down 33 per cent compared to last year.”

Tapp admits that given the uncertainty of return-to-the-office in the core, commercial real estate space has higher vacancy rates in terms of prior leases. “That would definitely be one blemish,” he says. “But I think that’s also the case in any major city in Canada. If you look at [other cities], everybody’s going to struggle right now because there’s less demand to bring people back to the office. I think that’s the national story — it’s nothing unique to Ottawa.”

Tech Power

Michael Tremblay, President and CEO of Invest Ottawa, tends to agree and says for the other side of business investment — businesses looking for places to set up shop and looking for capital — Ottawa is a very good bet.

“Knowing there’s so much uncertainty, I would pick [Ottawa] over a lot of locations,” Tremblay says. “We have an awfully good place for people to live, we have a lot of infrastructure in place for R&D, so from an investment perspective, if you’re looking for markets to place a bet on, recognizing that every single city on the planet has the same uncertainty of hybrid work, pick a location where people actually like to live.”

He says venture capital coming into the city has been “substantial” in the last 18 months in Ottawa.

“Look at where the Government of Canada is placing its bets when it comes to the technology sector,” Tremblay says. “They just put a block of money into Ericsson, they put a block of money into Nokia and there’s more coming. The reason is that the mandates are landing in Ottawa. They’re not landing in other markets at the same pace.”

He says Invest Ottawa attracts eight to 12 companies to the Ottawa area each year and they start out relatively small, but Ottawa also has the business advantage of having lots of big companies that are already here and growing.

“Ciena’s here, Ericsson, Nokia — even companies like Syntronics from Sweden. They have 800 people here now and they’ve only been here since 2016. It’s because our market is R&D-centric. Other markets are sales subsidiaries. Look at Microsoft and Google and Facebook and all the biggest tech companies — who do they lay off first? They lay off sales, service and support. What do they double down on? R&D. What is Ottawa known for? R&D.”

Tremblay says when you have a third of the economy wrapped up in government, tech and tourism, “that’s a pretty good basis for a strong, long-range resilient economy.”

Ottawa’s tech sector used to be focused on telecom, but that’s changed dramatically over the years, Tremblay says, to the point where it’s now centred on software companies.

“It’s diversified,” he says. “We’ve got a ton [of companies working] in defence and our biggest sector in Ottawa technology is software companies, not telecom. Telecom is second. So these are big changes. And there’s a benefit to our region, having the luxury of that kind of composition. With so much uncertainty everywhere in the world, I feel really lucky to be here.”

Tremblay says the fourth industrial revolution is not limited to technology — instead it combines the physical, biological and digital worlds. He was in Dallas, Texas, recently for a conference and delivered a talk on Area X. O — the Ottawa space where technology companies can develop, test and demonstrate their capabilities in an all-weather environment. He was asked by Texans, who’ve been dipping their toes in tech for the past three years, how Ottawa got into technology and he had to pause before he answered because the answer dates back 50 years to Northern Telecom.

Helping Innovation Along

Stewart says Ottawa can help itself by working to ease immigration rules, making it easier for companies to bring employees in from other countries, and it can also reduce red tape.

“I hear all the time from different manufacturers,” he says. “They say it’s the red tape in Canada and they’ll list very detailed issues. Finding ways to improve that could go a long way. It’s always one of the top things [companies] talk about.”

Tapp’s question for Ottawa is whether we’ll ever see National Hockey League games in downtown Ottawa. He also noted there are a lot of little businesses in the city centre that were built to service public servants.

“That would be places like laundromats, dry cleaners, coffee shops and things,” he says. “There’s certainly either reduced hours or pressure on those businesses because they’re not built for a two-day- a-week [workforce.] I come in to the office most days and on Fridays, it’s [pretty quiet.] Our Tim Hortons closes at 3 p.m.”

But, as he says, anecdotally, things are looking up.

“I do have the sense that momentum is building and more people are coming back, just by looking around,” he says. “It’s definitely not like it was a year ago and it’s a lot better than it was six months ago. I think some people want to be back in the office — they want to get some more human contact and in-person discussions and all the rest of it, so I’m more optimistic, at least on Ottawa and the general rebound.”