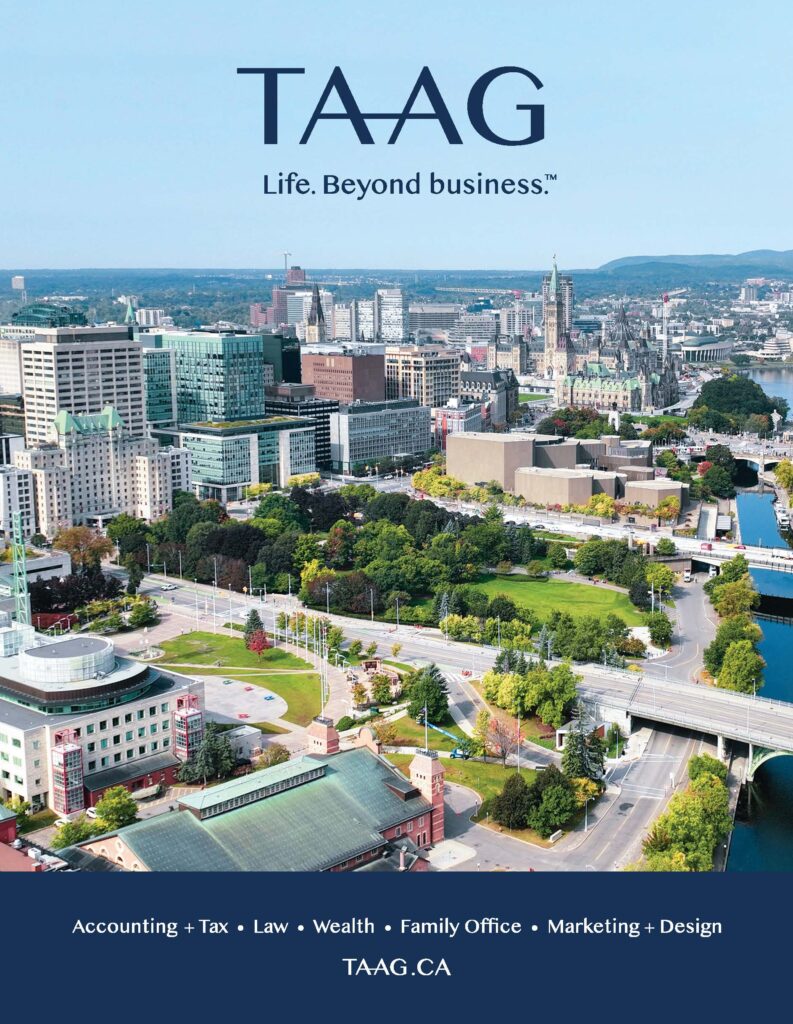

Downtown Ottawa Transformation

Aerial view of Ottawa's Cenotaph and Chateau Laurier on a sunny afternoon

MARY ROWE STANDS on the corner of Metcalfe and Sparks Streets, surveying her next project, which is to come up with a downtown Ottawa action plan.

She observes that it’s quiet where she is, and yet, when asked if she thinks downtown Ottawa is dead, Rowe, president and CEO of the Canadian Urban Institute, answered: “You can’t ever count a city out.” Then she told the story of New York City in the 1970s. It was in “deep trouble,” and on the verge of bankruptcy when the city approached the federal government for support.

“There’s this really famous headline that the New York Post ran, which was ‘Gerald Ford to New York: Drop dead,’” Rowe says. “The federal government basically said, ‘get yourself out of your own problems.’ And, you know, 50 years later, New York City is one of the greatest cities in the world.”

The urban advocate’s point that cities are resilient is even stronger for Ottawa, which, she points out, has “so many extraordinary assets.”

As she surveys the corner of Metcalfe Street, with a full view of Parliament Hill’s Centre Block to the north and the National Arts Centre to the east, while standing on the Sparks Street pedestrian mall, she says she’s looking at many of them at this very minute.

“You’ve got wonderful historic buildings, you’ve got already pedestrian-friendly areas, you’ve got a diversity of offerings — shops and restaurants and different kinds of services that are available to people. And increasingly, you’ve got more spaces for people to live in downtown,” she says, adding that the residential aspect is a really important lesson from New York City case, which is that any city that allows itself to be overly dominated by one user group or one industry group, fails. “It’s diversity that is the secret sauce of any city — diversity of user, diversity of use, diversity of experience, diversity of physical form.”

Mary Rowe, President and CEO of the Canadian Urban Institute

A critical point

Rowe says it’s a “really pregnant moment” for Ottawa and for many capitals like it, including Washington DC, because capitals have all of the ceremonial functions of being the centre of government and they also have a large segment of the workforce in the public sector. And just like with any one-business town, it’s clearer now than ever that it’s important to diversify.

She also says we have to set some frameworks and processes for a plan that will bring people back to the downtown core. She says we have to be imaginative and take “the long view — but not so long that it takes too long to [establish] these processes.”

Rowe moved to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina and lived there for a handful of years and saw how it clawed its way back to vibrancy.

“We have to think about is what kind of enabling conditions are we going to create here so that new things will emerge — things you and I haven’t even thought of yet,” she explains. “When you’ve got all these existing assets — you’ve got streets, you’ve got sidewalks, you’ve got buildings, you’ve got lobbies, you’ve got communal spaces, you’ve got you’ve got fabulous park spaces. You’ve got cultural spaces, civic spaces, you got all that to work with. To quote Arnold Schwarzenegger, how do you unleash hell in a good way? And that may mean rethinking rules, rethinking processes — financial institutions also need to rethink rules and need to rethink processes, and to think about different ways to get resources into the hands of social and economic entrepreneurs. I think this is our moment to build. A city is a habitat in which really great things grow.”

Asked about whether the federal government should mandate its employees to return to work more days of the week, Rowe said she does not think ultimatums are useful.

“I like to think that we find new ways to engage people who are employed by the government of Canada to think imaginatively with us about what kind of a city they want. What kind of work environment do they want? What kinds of collaborative opportunities exist? How can they make their spaces available for other uses?”

She says conversions of former work spaces to residential are critical, alluding to what happened in New York, after the terrorist attacks of Sept 11, 2001. Planners realized after the Twin Towers came down that there was an issue of monoculture in Lower Manhattan because the neighbourhood was dominated by the financial sector. When they knew they had to rebuild, they created the condition for more diversity, including residential. She says there were plenty of detractors of the plan, including urban planning goddess Jane Jacobs, and they were all ultimately proven wrong.

“You can actually create amenities, you can create really interesting environments where people want to live and work and play,” she says. “So we’re going to see the same transformation here — no question, in my mind.”

The question then becomes how to enable rather than obstruct that movement. “And how do we enable it to happen in a sustainable way?” she asks, noting that with a climate crisis on our hands, dense development is critical. “We’ve got to make it really easier, more interesting, more compelling to live close to one another, work close to one another, live close to where we work. Imagine if this was Burning Man and we were trying to build [downtown] on the desert. We’re not. We’re here, with extraordinary built assets across this country. And the question is, how do we leverage them?”

Rowe notes that Ottawa is a city that is “manageable” in size and that means there are a lot fewer reasons to say ‘No, we can’t do X, Y or Z.’

In addition to converting some of Centretown’s cavernous unused office buildings into residential offerings, Rowe says the city also needs to rethink, at least for the short term and maybe even for the long term, what the tax structure looks like for investment.

“Do we need to rethink property tax distribution? Probably,” she says. “Do we need to rethink how the federal government contributes to the tax base of Ottawa?”

Rowe notes that a lot of these problems existed before the pandemic, but the pandemic increased their urgency.

“Never waste a crisis,” she says. “Is it time to reorganize how we invest in these things, how we structure these things and how we pay for them. A dilemma you’ve got across the country is that municipal budgets are spread very thinly as they’re still dealing with the impacts of unprecedented expenses in EMS (emergency medical services) and stuff like that through COVID and basic services. And then they’re staring down the erosion of the commercial tax base because people are not just not occupying buildings, they’re giving up commercial leases.”

She says urban environments have been made possible by municipal services that have historically been funded off the property tax, and then some development charges, and the odd grant.

“It’s probably not the most sustainable way to create thriving urban environments,” Rowe says. “So we got to rethink that. We’re talking to Washington, DC, we’re talking to other capital cities who also have these challenges, to figure out if there’s a different way to do the math.

“And what we really need is engagement — and all of us working collaboratively.”

Work so far

MP Yasir Naqvi’s task force on downtown revitalization was an effort in collaboration, and it pulled together considerable input from residents as well as an admirably diverse range of task force members. But while it had planned to release a report in early summer, it remained held up in late October.

Hugh Gorman, a member of the task force and the chair of the Ottawa Board of Trade’s economic development committee, says Naqvi’s report will bring together a number of good ideas for the short and longer term, but Gorman feels that in the meantime, there are some measures that could be acted upon now.

“I worry deeply about downtown,” Gorman says. “This is why I was so appreciative of his initiative.”

The Ottawa Board of Trade has come up with five pillars it feels must be part of a downtown revitalization plan. Those include:

- Affordable, walkable communities;

- Efficient government approvals at all levels, including the fast-tracking of business permits, and a reduction or elimination of development charges for converting offices to residential, especially for affordable housing;

- Investment in the public realm;

- Encouraging employment;

- Creating safety and security for employees, visitors, business owners and residents.

While some of these pillars will take time to develop and initiate, there are some things that can be done right away, Gorman notes.

“We could completely eliminate development charges and fast-track every approval for any type of housing, but specifically affordable housing in the downtown core,” he says. “I can tell you there are projects in the private sector that are on hold because of those. We just had an announcement that the feds are going to not require GST for purpose-built rental housing. The economics of rental inventory compared to condos does not make any sense so what happens with that is that it gets reflected in the rents or alternatively, as the case is now, nothing gets built because the math doesn’t work.”

The financing piece, as raised by Rowe, is another one. With increases in construction charges, Gorman, who is the CEO of Colonnade BridgePort, a real estate and investment company, says no one can get financing for projects. He says combining the elimination of development charges with the GST reduction would see some projects start up again.

What the future holds

Regarding the plan she’s been asked to produce, Rowe says the planning process should be exciting.

“Some of my best friends are planners and some of my colleagues are planners, and we run processes that advocate for planning all the time,” she says. “Planning doesn’t have to be a prescriptive, dead or deadening process. It can be an enlivening, inspiring, engaging and permissive process. And I think that’s where these kinds of efforts involving all these different stakeholders become gardens for exploration and new thinking, and less about what that can’t be done.”

Rowe says initiatives such as efforts to rename a part of Centretown SoPa (meaning south of parliament) are just the kind of thing downtown Ottawa needs.

“This kind of self-organizing is really critical,” she says, adding that Ottawa restaurateurs were first to figure out they could create their own delivery services, which they did, keeping the money in the city, instead of sending portions of it out of the country to the multinational app owners.

In tandem with the revitalization plan being developed by the Canadian Urban Institute, Ottawa is one of three cities to be part of a new global effort, led by the World Economic Forum’s newly formed Alliance for Urban Transformation. The alliance connects urban innovators and entrepreneurs to new markets while trying to build more resilient local economies. It came out of efforts to help San Francisco rebound after the pandemic and that city will be the first test case for its work. Ottawa and Detroit are the other two. Invest Ottawa, the city’s lead economic development organization, is one of two chairs of the alliance.

Rowe says investing in community and people is key. And what does she say to those who want to help in efforts to revitalize downtown Ottawa?

“Come on down. Petula Clark was right. When you’re alone, and life is making you lonely, you can always go downtown,” she says, quoting lines from the singer’s famous song, Downtown. For those who want to make a difference, she recommends starting with the downtown library to see what’s happening, or visiting the business improvement areas’ offices (though she wants to rename them business innovation areas.)

“On-the-ground engagement is really critical. Start spending your money locally and start talking to folks about recommitting themselves to the vibrancy of the city.”